Voices of the Earth - Sugarcane

This blog is the second of seven reflections, on the healing power of plants. It is part of Global Generation’s Voices of the Earth Project, supported by The National Lottery Heritage Fund. The blog is written by Malaika Bain-Peachey, one of the Global Generation garden team, with thanks to Eben Lewis, who is one of the Voices of the Earth Fellows. Eben asked an important question. How far are we prepared to go, in terms of looking into the darker history of plants? Eben is a young sound producer who created the audio file you can find at the end of this post.

Notting Hill Carnival this year was the first in its 50 years to be held online, due to the current situation of the coronavirus pandemic. The organisers decided, mostly for the safety of the community’s elders, to turn the street celebration into a digital experience, making the event available to a wider audience internationally. As I immersed myself in playlists curated for the bank holiday weekend, I closed my eyes and imagined myself wandering between sound systems, accumulating glitter and paint as I danced with other festival-goers admiring the majesty of mas costumes along the way. I snap back as I hear ambassadors speak more of the history of carnival and its Caribbean roots.

Photo Credit: United Colours of Mas Notting Hill Carnival, 2018

In the 19th century, French colonisers and landowners would hold a masquerade event which, unsurprisingly, excluded and mocked slaves. The enslaved peoples would hold their own satirical mas and don costumes to mimic the masters, weaving in West African and Indigenous attire. After emancipation, ex slaves would also cover themselves in molasses, a major export of sugarcane plantations, as a statement highlighting what they endured. This celebration and rebellious act has become part of the Trinidad & Tobago J’Ouvert carnival tradition of covering our bodies in paint and mud, a less sticky stand-in today for the molasses of old.

Molasses. I try to conjure the smells and tastes of Carnival from the sofa in my living room. I suddenly catch a distant whiff of smoking drums and grills with the spicy, pimento scent of jerk, and I just about muster the memory of my first sip of rum punch.

I flash back to the best sip of rum I ever had, from a bottle I bought in a French supermarket. The top of the branding label reads “Martinique” and illustrated underneath it is the artist’s impression of the main house the sugarcane plantation owners inhabited. Before I know it I am scanning every shelf in this section. One label barely hosts any writing at all, but instead curved on the face of the bottle is a colourful illustration of a black woman with a headwrap, like those worn by women on the plantation who were once responsible for extracting the sugarcane molasses to make this libation.

Here I am in a French supermarket, the likes of which are found all over Martinique. An island territory that is still to this day a part of France. In my hand, this vessel contains fermented and distilled molasses. This bottle is a portal, a telescope into history across oceans. I peer through and immediately I am struck by the rich soil of lands fertilised by the bodies of Caribs and Arawak people, and forcibly farmed by West African slaves for centuries. A crop, whose sweetness is internationally enjoyed, has its roots earthed in bitter stories of brutality, torture, child labour, death and immense suffering. Sugarcane was, and in many places continues to be, cultivated: in neighbouring islands from Jamaica to Barbados, to the fields of the deep south of America, and in acres upon acres in Central and South America. Cambodia, Thailand, India, and China produce and export sugar globally too. I can’t help but wonder how the bloody past lives on in these farms through exploitation and expropriation.

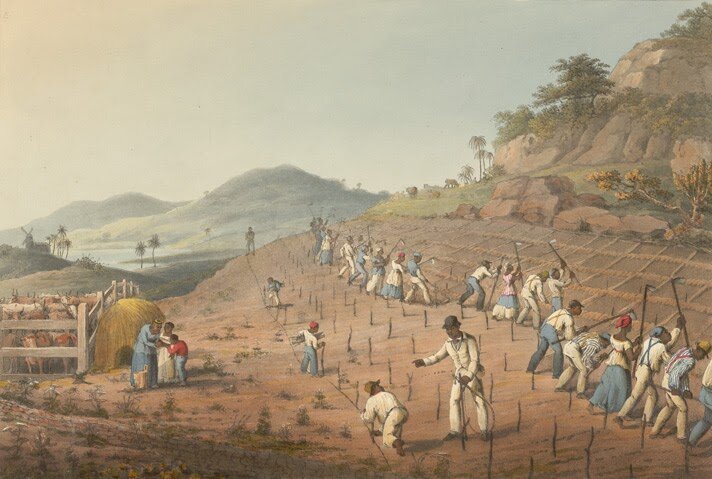

Aquatint by William Clark, 1823. Enslaved people working to prepare the fields before the planting of sugar canes on the plantations drawn on Weatherill's Estate in Antigua. Children had to mark out the areas to be hoed. Part of the British Library’s “Caribbean views: the full collection” online gallery exhibition.

My journey into sensory memories of Carnival takes me back to its root and to my ancestors. People surviving genocide, a racial hierarchy, a hostile environment, and an economy built on exploitation. All this twisted in the cells and fibres of a simple grass-like plant.

A plant that I had otherwise forgotten until a couple of months ago when a young man, Eben, our sound engineer, stepped into The Story Garden and asked a loaded question. How far are we willing to go? He was referring to the Voices of the Earth project, and choosing plants that we wanted to explore. Eben’s inquiry was a fork in the road that would lead us all down a less trodden path with thorns and overgrown vines; we would have to tread carefully and firmly onwards together.

Here there was something deeper to explore beyond the simple healing or nutritional properties of a plant. On this path was the power of a plant to confront wounds that haven’t healed, wounds that weep and sting with every headline from Minneapolis and Kenosha, as hashtags remind us Breonna Taylor’s murderers are still roaming free while those of us living in black and brown skin are not. Wounds that no salve can soothe when the Windrush generation is betrayed and deported before our eyes.

I thank Eben. In proposing sugarcane be part of our journey, he created an opportunity, an invitation to reflect. While we celebrate these plants, are we ready to meet our collective history embedded in their DNA? The answer, for me, is yes, and the time to do so must be now.

You can listen to Eben’s audio piece here:

This sound design, by Complicité sound designer Daniel Balfour, was created out of the work of children, young people and adults involved in the Voices of the Earth Project.

Each of the seven Voices of the Earth audio pieces were created as an invitation for you to spend time in Camden’s Green Spaces, listening to nature’s voices. Download the audio map here.

Meet our second cohort of earth build trainees! Their focus has been on all things wood, including green woodworking and the timber construction of the kitchen. They have learned on the job, while working on our sustainable natural build construction project to create our first permanent community garden, at the #TriangleSite.